While many focus on the front of the button, some manufacturers were paying careful attention to what goes on the back. At the turn of the 20th century, the verso of the button might contain an image or maybe a logo, text about the manufacturer, or advertisements for other products. These images on the reverse are known as back papers.

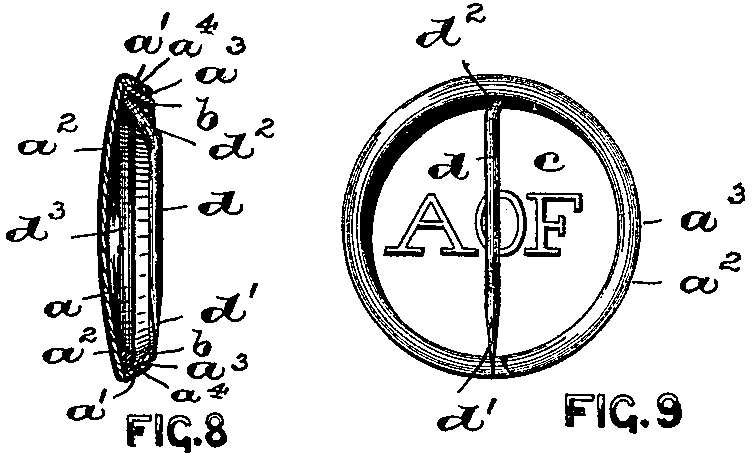

Back papers began as a way to display patents on button, pin, and badge designs. The patented design for buttons we use today stems from a patent filed in 1896 by George B. Adams. In this design, illustrated are back papers with an image of a flag or text behind the area of the pin.

In the 1800s, owning a printed image was coveted. Trading cards were collectible items and the pin-back button was making its way into the same industry. With an increase in the collectibility of buttons, manufacturers were interested in finding ways for customers to know who made the button so that customers would come to them for more like it.

The Walter N. Brunt company began producing buttons with back papers that displayed their company name, addresses, and later, union bugs or patent numbers. The Green Duck Company jumped in on the trend in the 1920s by adding their company logo, an illustrated green duck, along with the text. Patent information continued to be presented on the buttons to keep anyone from reproducing their product without permission.

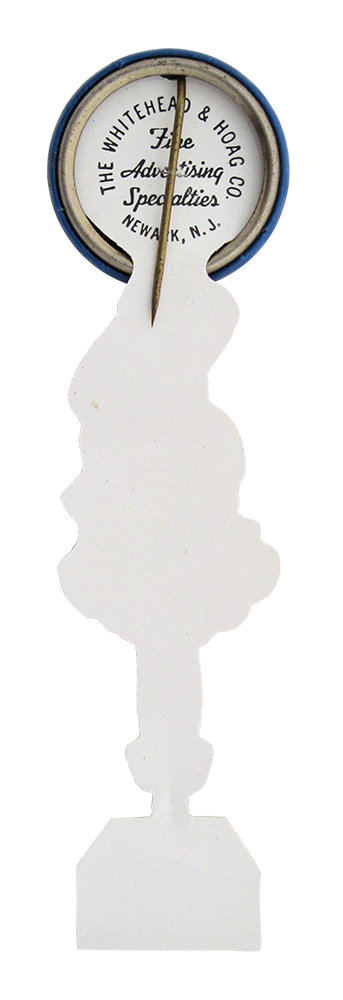

The most prolific in back papers was advertising specialty manufacturer Whitehead & Hoag. Whitehead & Hoag acquired three major patents on the design and manufacturing of buttons between 1892 when the advertising company was formed and 1902. Whitehead & Hoag picked up many clients including commercial businesses, both major political parties, causes like socialists and prohibitionists, and clubs. They expanded their sales offices from one small office in New Jersey to locations across the United States, England, Australia, and Argentina. In 1896, William McKinley included the political wearable pinback button and used them for his political campaign, starting a long trend of political button memorabilia.

As buttons continued to be trendy, more and more button manufacturers began to appear. The race to get buttons into the hands of customers before a competitor was a factor in the business practices of the back paper printing or stamping. Along with the need for speedy delivery, the button process changed as the plastic and metal industries boomed. The cost of manufacturing became cheaper and easier to mass produce buttons. With a simple tin or steel back, the desire for custom back papers diminished and any patent or manufacturer information was relegated to the side edge of the main image, presenting a much smaller nod to who made the button. Many of the original pioneers were aging out of the button industry and the manufacturing giants were beginning to change hands to younger entrepreneurs.

The last known back paper address for the Brunt company correlates to the mid-1920s, suggesting the company continued to feature back papers at this location until the papers ran out. Whitehead & Hoag still featured their name in back papers through the 1940s. In 1953, with the death of the last surviving elder Hoag, the company featured none of the original families on the board. Whitehead & Hoag was purchased by competitor Bastian Brothers and the name was phased out.

Buttons in the museum manufactured by Whitehead & Hoag Company

Buttons in the museum manufactured by Brunt

Buttons in the museum manufactured by Green Duck

Sources:

Brandvold, B., 2015. A Study of Western Button Manufacturers. [online] Electionmontana.com. Available at: <http://www.electionmontana.com/a-study-of-western-button-manufacturers/…; [Accessed 15 July 2022].

Hake, Ted., 2015. Whitehead and Hoag company history. Retrieved from http://www.tedhake.com/viewuserdefinedpage.aspx?pn=whco

The Norris Peters Company, 1896. Patent No. 564,356. [online] Patentimages.storage.googleapis.com. Available at: <https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/77/bb/ad/2defd6c4bc539d/US5…; [Accessed 15 July 2022].