Pinback buttons have a long political history. The earliest buttons and badges were used in political campaigns, a tradition that has continued into the 21st century, cementing the pinback button as a staple of political symbolism and activist ideology. Because they are inexpensive to produce, pinback buttons are considered a cheap and effective way to advertise for a political cause while allowing activists to quickly identify fellow members. Buttons offer the wearer a sense of engagement while acting as a visual symbol that the wearers are fighting for a cause. They also allow the wearer to visually connect with other activists, which can promote a sense of community with members personally unknown. The idea of wearable activism has shaped the pinback button into a staple of political activism, with a variety of campaigns and movements utilizing buttons in their everyday work.

One movement that has contributed to a prolific amount of political buttons is the Civil Rights Movement.

The Civil Rights Movement was a variety of activist movements fighting for full political, social, and economic rights of African Americans. Officially dated from 1946 to 1968, activism focused on the civil rights of the black community began before slavery was abolished and still continues today. In order to better understand the Civil Rights Movement, it's important to discuss the history of racism and the fight for civil rights in America. Alongside the creation of the United States as a country, abolitionists were working to eliminate slavery and racial injustice. During the Civil War, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, codifying the thirteenth amendment into the Constitution and declaring slavery illegal in the United States. Slavery would not be ended fully until June 19th, 1865, when Union soldiers arrived in Galvenston, Texas, to fully enforce the emancipation of slaves.

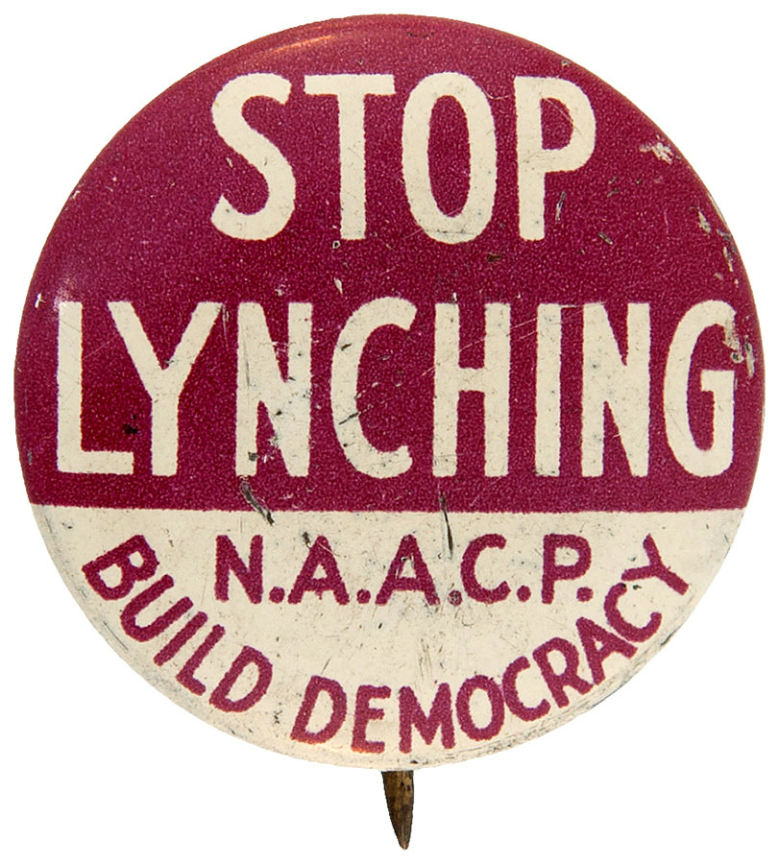

Even after emancipation, the black community was far from being truly free. In the South, Jim Crow laws were created to enforce racial segregation while systematically ensuring that the black community remained disenfranchised. The white community maintained their political, social, and economic power. While the South is commonly attributed to the subjugation of the black community, it's important to also discuss that systemic racism was also prevalent in the North as well, including, but not limited to, segregated businesses, schools, colleges, and housing opportunities. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the nation’s largest civil rights organization, was established in 1909 to enforce the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. They have a long history of legal activism, working to carry out the rights of African Americans through the legal system. From their founding, the NAACP fought against the practice of lynching, a repression tactic common throughout the country. In 1937, with the support of the NAACP, the Costigan-Wagner Bill, an antilynching bill, was reintroduced into Congress. Younger members of the NAACP sold these ‘Stop Lynching’ buttons as a way to influence public opinion for this antilynching legislation.

A culmination of the political, economic, and social injustices against African Americans led up to the Civil Rights Movement, sparked by the lynching of 14-year-old Emmet Till in Alabama in 1955. At this point, civil rights groups increased their political activism with demonstrations across the south. CORE, The Congress for Racial Equality, an organization that formed in Chicago in 1942, focused on integration through nonviolent action and civil disobedience. CORE supported Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during the Montgomery Bus Boycotts in 1955, as well as organized the Freedom Rides in 1961. The Freedom Rides were an effort to protest segregated interstate travel by bussing a group of civil rights activists through the deep south. Freedom Riders were met with heavy violence from white individuals who opposed integration and the violence enacted on the riders was displayed across the country by the media. The button seen here promotes both The Freedom Rides and CORE.

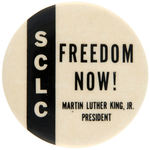

The SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, formed in 1960 with a focus on exposing injustices and calling for direct action through the mobilization of local communities in nonviolent protests. They organized lunch counter sit-ins, contributed to the 1961 Freedom Rides, and sponsored the 1963 March on Washington. In 1964, CORE and SNCC, along with other activist groups, established the political campaign “Freedom Summer,” working to register black voters across the south. While working together, both CORE and SNCC produced black and white “Freedom Now” buttons for campaign workers to wear.

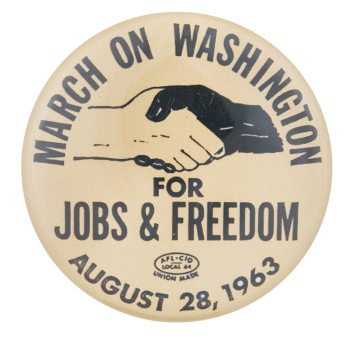

On August 28, 1963, the historic March on Washington for Jobs & Freedom took place. The march was originally conceived in 1941 by A. Philip Randolf as a “march for jobs” to protest the discrimination of Africans Americans from the jobs created by WWII and the New Deal. The march was put on hold due to the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC), but when the FEPC dissolved five years later, Randolph began re-planning the march. In the 1950s, Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) were also planning a march for freedom, and it was decided to merge the two marches into one unified event. Six prominent civil rights leaders worked together to organize the march; Randolph (Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters), Dr. King (SCLC), Roy Wilkins (NAACP), James Farmer (CORE), John Lewis (SNCC), and Whitney Young (National Urban League). A quarter-of-a million people participated in the march and gathering at Lincoln Memorial, where Dr. King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech was given. There were multiple buttons created and worn for this historic event.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was finally signed into law by then President Lyndon B. Johnson after being stalled in the judiciary committee by segregationist senators. The Civil Rights Act included provisions barring both discrimination and segregation in public facilities, education, jobs, and housing, as well as established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and a federal Community Relations Service for assistance to local communities on civil rights issues. Unsurprisingly, the implementation of the Civil Rights Act was met with resistance in some communities. Confusion over whether the bill included private institutions led some public venues to attempt transformation into private clubs, but the Supreme Court deemed these attempts unconstitutional and upheld the Civil Rights Act’s equal access provisions. What the Civil Rights Act lacked was strong provisions to ensure equal voting rights. After facing more violence against civil rights workers after the passage of the Act of 1964, six hundred activists set out on March 7, 1965, to march from Selma to Montgomery. When crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge, hundreds of state troopers and deputies brutally attacked the activists, and this violence was broadcast across the media, dubbed as “Bloody Sunday.” This event prompted more civil rights activists to join in the cause which led to the passing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

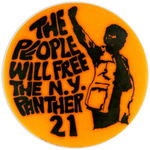

While these two important pieces of legislation were now made into law, the fight for full civil rights went on. The rise of the Black Panther Party in 1966 presented a change in tactics by some civil rights activists; there was a move away from nonviolent protests to more revolutionary practices. The fight has continued on throughout the decades, most recently through the Black Lives Matter Movement, which began as a social media movement in 2013 in response to continued police brutality and murder of black men, women, and children by the police. In 2020, in response to the murder of George Floyd, the BLM movement gained momentum as activists protested in cities and towns across the world against police brutality and racial injustices. Throughout the decades, activists fighting for civil rights have created amazing buttons to help both promote their causes as well as visually connect movement members across the nation.

Sources

Brooklyn Public Library's Brooklyn Collection. (n.d.). Civil Rights in Brooklyn Primary Source Packet. Retrieved on September 27, 2020 from https://www.bklynlibrary.org/sites/default/files/documents/Civil%20Righ…

Bynum, T. (2009). “We must march forward!”: Juanita Jackson and the origins of the NAACP youth movement. The Journal of African American History, 94(4), 487-508. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25653975

Hake's. (2015). Rare "Stop Lynching NAACP Build Democracy" Litho Button. Retrieved from https://www.hakes.com/Auction/ItemDetail/103571/RARE-STOP-LYNCHING-NAAC…

History.com Editors. (2009, October 27). Civil Rights Movement. Retrieved September 27, 2020, from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/civil-rights-movement

Janken, Kenneth R. “The Civil Rights Movement: 1919-1960s.” Freedom’s Story, TeacherServe©. National Humanities Center. Retrieved September 27, 2020. <http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1917beyond/essays/cr…;

Khan Academy. (n.d.). The Civil Rights Movement: An introduction (article). Retrieved from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/postwarera/civil-righ…

Majekodunmi, N. (2016). Talking pieces: Political buttons and narratives of equal rights activism in Canada. Journal of Black Studies, 47(7), 753-772. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/26174184

Mack, D. (2019, May 17). Freedom Rides (1961). Retrieved September 27, 2020, from https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/freedom-rides-1961/

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. (2020, August 04). Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Retrieved September 27, 2020, from https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/congress-racial-equalit…

Miller, M. (2020). Change agents. Retrieved from https://www.gettysburg.edu/news/stories?id=482b3801-20de-4845-9700-d0a3…

NAACP. (n.d.). The March on Washington. Retrieved September 27, 2020, from https://www.naacp.org/marchonwashington/

Speltz, M. (2016, October 26). An Activist's View of the Civil Rights Movement. Retrieved September 27, 2020, from https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/an-activists-view-of-the-civil-rights-move…

Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement. (n.d.). Pins of the Freedom Movement. Retrieved September 27, 2020, from https://www.crmvet.org/info/pins.htm